What does it mean to be an American?

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in Colorado, where five talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people representing a diversity of experiences and backgrounds in gender identity, physical ability, whether they are Indigenous, native born, a refugee or an immigrant without legal status—to ask what it means to be an "American.”

NPR Next Generation Radio’s anya quesnel shares the story of Anna Sofia Vera, a dual citizen of Chile and the United States, who explores what it means to belong when roots in two countries lead to an ever-shifting definition of home.

Illustration by Eejoon Choi

To be American is to ask what it means: How a dual citizen finds home in herself

Anna Sofia Vera holds two passports — Chilean and American — which made migrating to the United States for college easier on paper. Yet her sense of national belonging is more nuanced.

Vera was born in Santiago, Chile, to a Chilean father and an American mother. She lived all of her life in South America before coming to the United States in recent years.

Vera’s parents were divorced early on in her life and she said that their nationalities created even more divisiveness in her and her sisters’ lives growing up. She remembers experiencing “some of America” through subtle cultural differences like celebrating Thanksgiving, which she did not see her Chilean peers and their families do. Growing up, she became her own compass for navigating questions of identity through the arts.

Two passports, two languages and endless questions

Anna Sofia Vera spends time with her cousins at Sunset Park in Littleton, Colo. She finds outdoor spaces to be peaceful yet energizing. (Photo: Kevin Beaty)

“I love music and theater. Those are my big venues of self-expression,” she said.

In Vera’s experience, being American is a label other people put on her, especially when she is outside the borders of the country.

“When I go back home, some friends call me the gringa, which is what we call Americans in our country and when I come to the U.S., people see me as a foreigner,” she said.

When she moved to the U.S., she felt like her nationality was the first and sometimes only aspect of her that people saw, but she knows there is so much more than that.

“I think that our identities are formed by our experiences and relationships and new learnings.”

Life at an American college

What Vera named “the privilege of having a U.S. passport” came fully to light when she moved to Colorado for college. She’s now entering her senior year.

“I can legally work off campus and move around the country and not have to explain to the government or to the school what I am doing or why I am doing it,” she said.

In the U.S., Vera said she feels most at home surrounded by other international students. She acknowledges a shared sense of being outsiders that makes bonding easy. For example, her international student peers must get creative in their care for one another in order to build support systems that do not necessarily exist for them in this country.

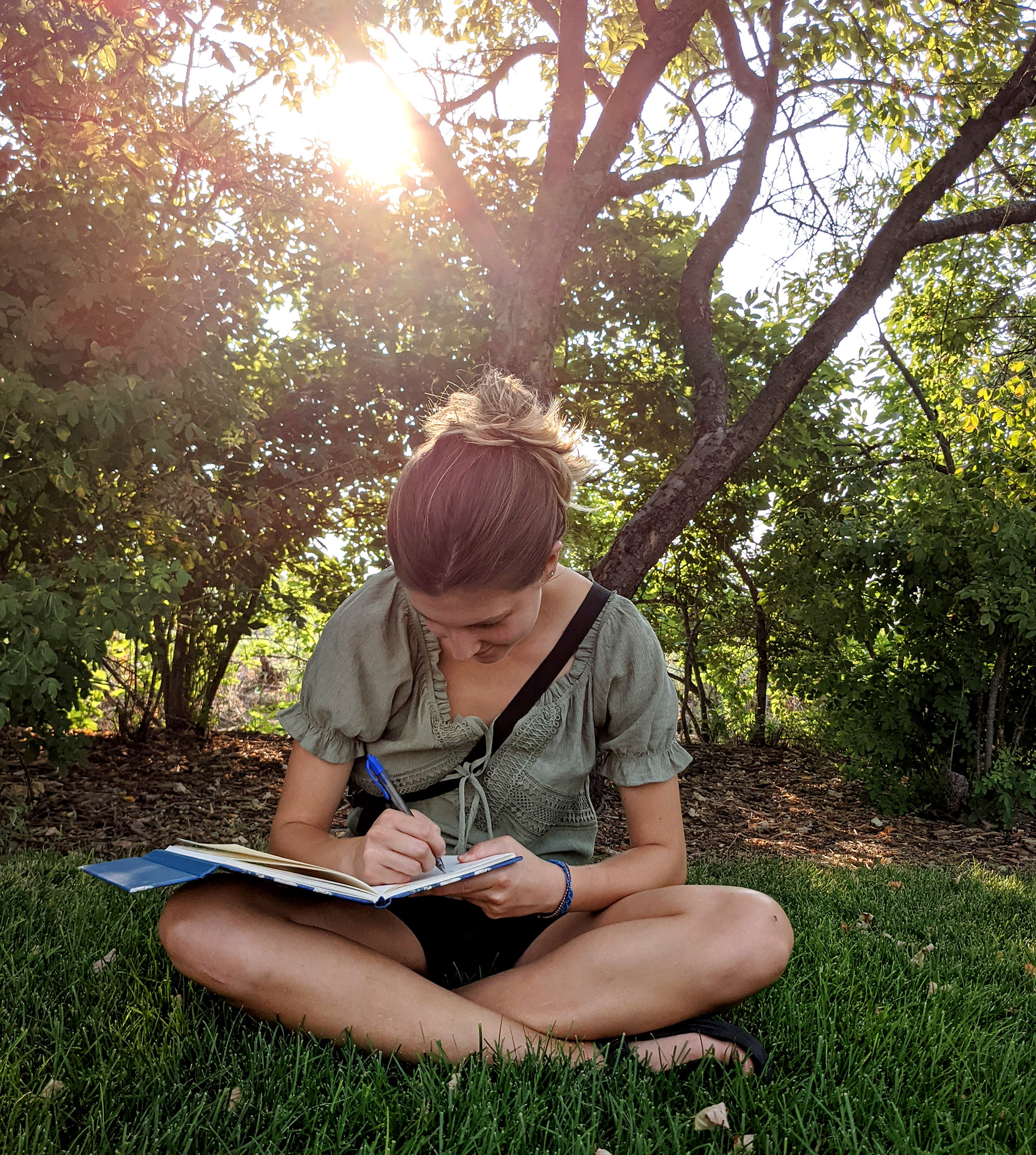

Vera says that finding time for herself and to connect with Chile through music and language has been very important during her time in the U.S. (Photo: anya quesnel)

As an environmental science major, Vera is passionate about environmental justice in both Chile and the U.S. She noted her home country is considered a “developing country,” and that development often equates to exploiting the land and people.

“I had met activists back home, and I had met activists here who were able to make environmental justice an accessible issue,” she said. They can “move it away [from] the individual actions, and instead look at it as a systemic issue and how to address it through coalitions and activism and collaboration.”

Holding onto home in a pandemic

The nuances surrounding Vera’s national identities became more pronounced during the pandemic, when the school residences were closed and she had to stay with her grandparents in Colorado. Adapting to life in quarantine was challenging, as she felt culturally different from her family. She would have to intentionally carve out time for herself to connect with Chile however she could.

While she wanted to return home to Chile, her father warned that the economic downturn as a result of Covid-19 meant that she was better off remaining in the U.S. However, as Chile turns toward new political beginnings with a new constitution, Vera said she would rather be at home taking part in the demonstrations and being a part of the social justice movements there.

“If someone asks me where I am from, I’m from Chile. I’m Chilean. I then mention, maybe, that my mom is from the U.S. but that’s not my immediate response,” she said.

Given the choice, however, Vera would not give up her American citizenship. She acknowledges the privileges her status affords her, but she said loss of citizenship would not simplify how she understands her identity.

“I think that those identity conflicts or identity paradoxes will still remain,” she said, “even if the papers [are] not there.”

Vera thinks about terms like “family,” “belonging” and “home” expansively. These change shape depending on the spaces she is in. (Photo: anya quesnel)